Bible in Southeast Asia

Reflections, recollections, digressions, random thoughts, insights, etc. on how the bible can shed light on the culture, way of life, practices, customs, habits, virtues, vices, anxieties and hopes of South East Asians, especially Filipinos. [best viewed with Mozilla Firefox browser]

Wednesday, March 21, 2007

Seven Last Words at Divine Word Seminary Chapel

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

Where did Ancient Israel come from?

T o understand who we are, our behavior, our customs and practices, our ways of thinking, our tendencies, our values and vices -- in other words, our identity, it is important to understand our origins. Where did we, Filipinos, come from? Who were our ancestors? What did our ancestors look like? Their language? Their beliefs?

o understand who we are, our behavior, our customs and practices, our ways of thinking, our tendencies, our values and vices -- in other words, our identity, it is important to understand our origins. Where did we, Filipinos, come from? Who were our ancestors? What did our ancestors look like? Their language? Their beliefs?

Similarly, the question on the origins of Ancient Israel is fundamental to understanding Israel's identity, its religion, its values, and its faith in Yahweh.

Where did Israel as a nation come from?

o understand who we are, our behavior, our customs and practices, our ways of thinking, our tendencies, our values and vices -- in other words, our identity, it is important to understand our origins. Where did we, Filipinos, come from? Who were our ancestors? What did our ancestors look like? Their language? Their beliefs?

o understand who we are, our behavior, our customs and practices, our ways of thinking, our tendencies, our values and vices -- in other words, our identity, it is important to understand our origins. Where did we, Filipinos, come from? Who were our ancestors? What did our ancestors look like? Their language? Their beliefs?As we say in Tagalog, "Ang hindi marunong lumingon sa pinanggalingan, hindi makararating sa paroroonan" (A person who does not look back to where he/she came from, will not reach his/her distination)

Similarly, the question on the origins of Ancient Israel is fundamental to understanding Israel's identity, its religion, its values, and its faith in Yahweh.

Where did Israel as a nation come from?

The classical understanding is that Israel came from Egypt (based on Exodus), conquered the so-called Promised Land (based on Book of Joshua), and later on established itself in that land also called Canaan ruled by their kings, notably David and Solomon (as in 1-2 Kings).

This is the story that we get from the Old Testament. Yet we know today for a fact that the bible is not a history book nor is concerned of presenting historical facts and preserve them as historians do today. Thus, to rely solely on the bible to search for the historical origins of Israel is not enough. Extra-biblical literature (that is, written texts outside the biblical canon), archeological remains of the past, ancient inscriptions, monuments, and the like are further materials being examined to get a historical picture of the origins of Ancient Israel.

The Issue

The Conquest Model – William Foxwell Albright

For a summary of N. Gottwald's theory, click on this.

Sources:

John J. McDermott, What Are They Saying About the Formation of Israel? (New York/Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1998).

Anthony R. Ceresko, Introduction to the Old Testament: A Liberation Perspective (revised and expanded Edition;Quezon City

Randolf C. Flores, “Theories on Israelite Origins” (unpublished paper, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1996).

Here's an article in answer to that search for the the origins of Ancient Israel

The Origins of Ancient Israel

Summary /Excerpt by R. C. Flores, svd

(July 2004; updated 28 July 2006)

Summary /Excerpt by R. C. Flores, svd

(July 2004; updated 28 July 2006)

The Issue

The initial answer to the question above is that the Israelites came from Egypt. A group of descendants of Abraham escaped from slavery in Egypt under the leadership of Moses. They wandered for forty years through the wilderness; they crossed the Jordan River in the land of Canaan. After a series of wars against the natives of Canaan, they conquered all the Canaanite cities under the leadership of Joshua. The first half of the Book of Joshua recounts the total defeat of Canaan; the second half of the book describes the division of the land among the tribes of Israelites. The book ends with the whole of Israel coming together at Shechem for a covenant renewal ceremony.

As we however, open the pages of the Book of Judges, we get a very different picture. It begins with listing of places not yet conquered by Israelites, even territories mentioned earlier by Joshua as already occupied (compare Joshua 11:16-17 and Judges 1:9). Judges as a whole gives the impression of along, continuing battle between the newly arrived Israelites and Canaanites, who continually to hold on to much of the territory; and it is not until the beginning of the monarchy, in the Second Book of Samuel, that King David takes the city of Jerusalem from the Canaanites.

Besides the contradictions between the Books of Joshua and Judges, there are problems reconciling archaeological data with the stories in the Pentateuch, Joshua and Judges. For instance, the Book of Exodus describes a series of catastrophic events in Egypt (the plagues) ending with the death of the firstborn of the Egyptians. If all of these events did take place in the magnitude in which Exodus describes them and all within a short period of time, one would expect it to be recorded in some source other than the Bible. However, no Egyptian records, archeological or otherwise, mention the events of Exodus.

Concerning the wars and victories in of the Israelites in the Book of Joshua, archeological evidence does not support “lighting” or suddend and massive conquest of Canaan. Several cities mentioned as conquered, destroyed and burned by the Israelites show no evidence of destruction. Examples are the cities of Jericho and Ai. The popular story about walls of Jericho crumbling down (Joshua 6:20) could be anything but historical.

Theological rather than Historical Scholars acknowledge that the biblical story of the beginnings of Israel has a theological rather than historical purpose. It expresses the fulfillment of promises that God made to the chosen people—Abraham, Sarah and his descendants. The center of the promise was that God would give them a land of their own. If the biblical account of the origins of ancient Israel is not history in the modern sense of the term, what is the historical origin of these people? In order to understand better the world of the author, scholars are also interested to know where the Israelites came from. With the recent archeological discoveries in Palestine and in Egypt, scholars today have a wider view of the issue and have developed three models to explain Israelite beginnings.

The Conquest Model – William Foxwell Albright

The Conquest model is based primarily on the Book of Joshua. W.F. Albright, an American archeologist in the first half of the twentieth century was mainly responsible for articulating this model and finding archeological support for it. According to this theory, the story in the Pentateuch to Joshua is based on underlying history; the Israelites came out of slavery in Egypt and, after some years of migration through the desert, invaded Canaan from the east. Albright cited archeological evidence to support the historicity of the conquest. He pointed to excavations of several large Canaanite cities that showed evidence of destruction like Debir, Bethel, Lachish, and especially Hazor (see Joshua 11:11).

Albright’s views had been influential for many years. Even today, many Fundamentalists and conservative Catholics have cited him as proof that the Bible is historically accurate. There has, of course, been much archeological research since Albright’s time, and much of the evidence he used is no longer considered valid. The weakness of this model, as pointed above, is its inability to explain why some major Canaanite cities like Jericho show no archeological evidence of destruction and the and also the different account of the conquest in the Book of Joshua.

For a summary of the problem of the Conquest Model, click on this.

For a summary of the problem of the Conquest Model, click on this.

Peaceful Infiltration Model—Albrecht Alt

This theory maintains that the early Israelites were nomads from the surrounding regions who gradually and peacefully began to settle in the highlands of Canaan. As these settlements increased, there were occasional battles between the new Israelites and the Canaanite cities, and as the cities declined and Egypt lost control of Canaan, the new Israelite settlers became the dominant force in the land of Canaan.

Albrecht Alt, a German biblical scholar, developed this model based on the stories in Genesis about Abraham, Isaac and Jacob who were first nomads before they became Israelites. The early Israelites were also formerly nomads or semi nomads who had migrated into and out of Canaan on a seasonal basis long before they settled in permanent villages. With the decline of the Canaanite city-state system, they were able to occupy the lowlands as well.

The advantage of this Peaceful Infiltration model is solution to the problem of too bloody and violent beginnings of Ancient Israel. Moreover, this gradual process of migration parallels the modern experience of the many migrants all over the world. The problem, however, of this model is that it cannot explain why are the material culture and religion of the Canaanites and migrant Israelites similar if the two came from different cultural backgrounds. The theory also has to explain why the Bible tells a different story of Israelite origins.

Social Revolution Model—George Mendenhall and Norman Gottwald

The theory maintains that most of the early Israelites were not people who came into Canaan from elsewhere but were indigenous Canaanites. The lower-class Canaanites were heavily taxed by the Canaanite kings and had little control over their own lives, so they finally rose up in a violent revolt. The revolt was successful, and these people then established a new decentralized, egalitarian society in the highlands.

It was G. Mendenhall, in a 1962 article, who began to discuss the phenomenon of people politically separating themselves from the dominant rule in Canaan. In subsequent years, Norman Gottwald developed his model in much more detail. His 1979 book, The Tribes of Yahweh: A Sociology of the Religion of Liberated Israel, 1250-1050 B.C.E., combined extensive analyses of texts and archaeological data with a sociological study of changing societies.

The beginning of the Israelites can be traced back to lower-class Canaanites like peasant farmers, sheep and goat herders, itinerant metalworkers, priests renegade from the official urban-based cults, and mercenaries, and other nomads who were living in an oppressive Egyptian feudal system of the Canaanite city-states in the thirteenth century. These marginalized people wanted more freedom, economic and political independence from the city-states. They had withdrawn or fled from the oppressive economic and social conditions of the coastal plain and fertile valleys and settled in the rugged, rocky hill countries where sought to recreate new way of living characterized by equality, freedom, sharing goods, stronger family ties, respect for everyone, and belief in one God called El.

This newly formed egalitarian community is strengthened further with the arrival of a small group of refugees from Egypt under the leadership of a man named Moses. These refugees brought with them their stories and memories of a god called Yahweh, who had liberated from slavery and forced labor under the pharaoh. The Canaanites who had experienced similar situations of domination or virtual slavery adopted the Egyptian refugee’s story as their own. They also began to worship Yahweh as their patron deity who stands by the poor and frees the oppressed.

The Social Revolution model has been criticized for going too far beyond the evidence and for imposing modern ideology, particularly Marxist ideology, on the process. But it has been influential in leading biblical scholars to make more use of the social sciences and to focus attention on the Canaanites themselves as the possible people from which Israel emerged. Moreover, this model is relevant to the so-called “third world” countries characterized by massive poverty, economic injustice, and inequality; the many political, economic or religious refugees and displaced people around the world; indigenous and tribal minorities who had been forced in the past to go up in the mountains to avoid the oppressive system of the lowlanders; and the many urban squatters who are forced to be relocated far away from their places of work in the name of development.

For a summary of N. Gottwald's theory, click on this.

A. Ceresko follows the the model proposed by G. Mendenhall and N. Gottwald. It is for this reason that he suggests to read the Old Testament, in particular, the Pentateuch as a literature that records Israel's struggle for liberation. Israel's God has acted in history to liberate his people, to be free to worship him. The Pentateuch, therefore, is a protest literature to challenge an oppressive situation of the past, yet it is also testimony of Ancient Israel’s struggle for justice, peace, and integrity of life and creation.

Sources:

John J. McDermott, What Are They Saying About the Formation of Israel? (New York/Mahwah, N.J.: Paulist Press, 1998).

Anthony R. Ceresko, Introduction to the Old Testament: A Liberation Perspective (revised and expanded Edition;

Randolf C. Flores, “Theories on Israelite Origins” (unpublished paper, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1996).

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

Tax and Toll Collectors

"Many tax collectors and sinners came"

Read: Matthew 9:9-13

Since the Philippine government implemented a lifestyle check on its employees, eleven officials from the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR) face charges of graft and corruption at the Ombudsman. The current BIR commissioner is also battling charges of failing to collect the target P675 billion collection for this year. This department has always been a favorite "den of thieves".

In the world of the New Testament, the expression "tax collectors and sinners" (Mt 9:10) is common, almost like a slogan. Why are tax collectors sinners? Not all of them are corrupt (as there are a lot good souls also at the BIR).

The Greek word "telōnēs" usually translated "tax collectors" properly means "toll collectors".

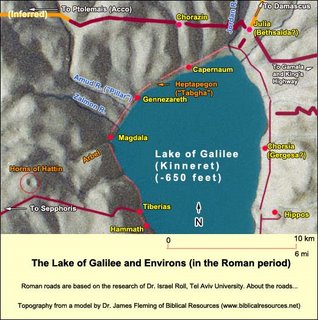

Matthew (called Levi in the Gospels of Mark and John) worked in Capernaum, Jesus' second hometown along the edge of the Lake of Galilee. This town was strategic as it was located along the major road of international trade between Damascus and Egypt. Goods and merchandise sold in other towns had to pass through Capernaum. Tolls had to be paid for goods entering and leaving Capernaum. Matthew was a toll collector who worked in the Capernaum custom house (someone like a customs collector today).

The strategic location of Capernaum,

situated near one of the main highways connecting Galilee with Damascus

situated near one of the main highways connecting Galilee with Damascus

Why are toll collectors called "sinners"? The rich and the educated, a minority in Jesus' day, routinely criticized toll collectors because such job was not honorable as collections were paid to the colonial power, Rome. Though against their will because they were Jews, they had to do the job to survive. Any extra amount came from tips from the merchants who passed through Capernaum. Toll collectors rarely could cheat because of the efficiency of the auditing of the Roman empire.

Toll collectors were not sinners because they cheated on their job. They were simply stereotyped as sinners because they worked in such a "dirty" job. We can’t but admire Jesus who ate with them and considered them as friends.

Capernaum today, once a busy transit fishing port

For an advanced study of this topic click on this site.

For news (in Tagalog) of the on-going SVD Chapter, click on this blog.

Monday, June 12, 2006

Abbreviated mission assignment and more SVD Chapter news

Here's a first hand report on what's going on in the SVD 16th General Chapter, grabbed from Munting Mensahero (Little Messenger), an email news written by Jerome Marquez (delegate of Philippine Central Province).

Note: News in Tagalog.

Click: Abbreviated mission assignment and more SVD Chapter news

Note: News in Tagalog.

Click: Abbreviated mission assignment and more SVD Chapter news

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Edilberto Sena and Jose Boeing, SVD Receive Death Threats

The two gentlemen are actively involved in the protection of the environment and biodiversity in the Diocese of Santarem of the Amazon Region in Brazil. Edilberto Sena, founder and present director of Radio Rural, uses the air to educate the locals on the vital importance of ecological balance. Jose Boeing, a missionary of the Society of the Divine Word is the zonal coordinator for its office responsible of promoting justice, peace and integrity of creation.

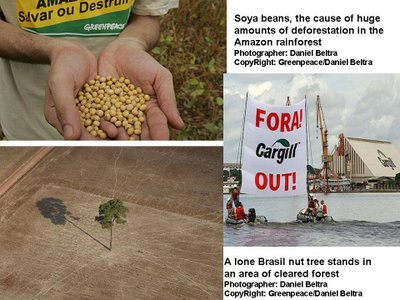

The two gentlemen are actively involved in the protection of the environment and biodiversity in the Diocese of Santarem of the Amazon Region in Brazil. Edilberto Sena, founder and present director of Radio Rural, uses the air to educate the locals on the vital importance of ecological balance. Jose Boeing, a missionary of the Society of the Divine Word is the zonal coordinator for its office responsible of promoting justice, peace and integrity of creation.They are being accused of conspiring with Greenpeace activists who are currently waging war against Cargill, the leading exporter of Soya. Soya expansion has been blamed as one of the leading causes of the deforestation in the Amazon.

The website of Associazione Macamondo reports that a certain "community" in Orkut under the name "Fora Greenpeace" (Greenpeace Out) wrote: "We want to kill Edilberto Sena and Fr. Boeing for the good of Santarem."

These and other more threats have prompted members of Society of the Divine Word where J. Boeing belongs to write this open letter authored by A. Pernia, the current Superior General.

Please take time to read and forward this letter to others (pls. click to forward).

As missionaries of the Society Divine Word (SVD), gathered together in Rome for the General Chapter, an international assembly of SVD brothers and priests, we are pained by the recent events occurring in the Amazon Region of Brazil. We refer to the death threats received by Fathers Edilberto Sena and Jose Boeing SVD. Likewise we are deeply affected by the pressure exerted upon the two bishops and all the organized social movements of the Diocese of Santarem. The work they are doing is in line with the global mission and vision of the SVD.. As a gesture of solidarity with them and with all the people who fight for justice, ecology and the integrity of creation, we ask:Blessed are those who are persecuted for justice' sake,

for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven (Mt 5:10)

- for the possibility of an open dialogue with Cargill regarding problems related to agri-business. In this dialogue all concerned parties should be represented, as should other representatives of civil society.

- or the immediate investigation of the recent events by the Ministry of Justice, the Public Ministry and the Federal Police.

- for the protection of the concerned individuals threatened by death.

- that Cargill present the studies on the environmental impact of its establishment in Santarem and legalize its status as demanded by national and international laws on human rights.

- for respect towards the indigenous peoples in the Amazon region, and for the preservation of the integrity of the forest.

Fr. Antonio Pernia SVD

Superior General and President of the General Chapter

On behalf of the 149 participants who represent the 6102 Divine Word Missionaries working in 70 countries worldwide